- Have any questions?

- +34 951 273 575

- info@diningsecretsofandalucia.com

Taste of Autumn – Reservations… please!

30 October, 2018

Stunning Rio Carnival dancers take over Marbella’s Posidonia restaurant

13 November, 2018FIONA Dunlop is a British food and travel writer, blogger and photographer who has globe-trotted for decades from successive bases in Paris and London.

Andalucía has long been a much loved destination where she often retreats to her house amid the olive groves. After writing travel-guides and features on art, design and travel, her passion for food gained the upper hand. The publication of New Tapas (2002) followed, then The North African Kitchen (Medina Kitchen) and Mexican Modern (Viva la Revolucion!). As well as contributing to the national press (FT, Telegraph, Independent, Guardian) and magazines, she has authored National Geographic’s guides to Spain and Portugal and worked as a guest lecturer on their expeditions.

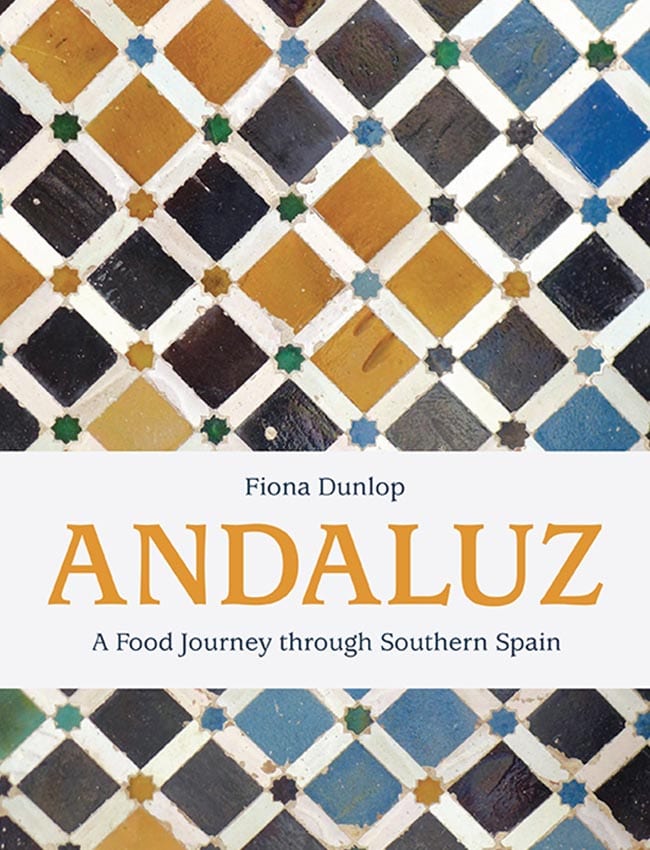

Her latest book, Andaluz: A Food Journey through Southern Spain, contains 304 pages of recipes, flashes of landscapes, life and people across Andalucia. The book is available on Amazon now. Read an introductory chapter, which chronicles Fiona’s love affair with Andalucia here, ahead of the publication of exclusive recipes from the book in the next issue of the Olive Press on Wednesday:

3. ANDALUCIA & ME

The first time I ever sighted Andalucía was back in the 1970s. As you did in that free-thinking, free-moving, post-hippie era, I set off with two fellow students in a battered 2CV to rattle all the way from Montpellier, where we were fine-tuning our French studies, south to Marrakesh – about 2000km. As soon as we had cut through the dramatic Sierra Morena, the gateway to Andalucía from the monotonous plains of La Mancha, I was transfixed. Here was a wild, grandiose landscape, a universe of elemental, raw escarpments either glowing with chalky limestone or soaking up the light with flinty shale, interspersed with carpets of olive-trees or lush ravines. It was magical.

Crunching gears asthmatically, our primitive car bumped around the deserted bends before we lost our way, but eventually reached Algeciras and the car-ferry across the Strait of Gibraltar. Andalucía’s rolling sierra studded with whitewashed fincas and goats, its roadside ventas, palm-trees, donkeys, fried fish and the gut-rot red wine of the time all left an indelible mark. It felt almost as exotic as Morocco, that mythical neighbour where the haunting muezzin sent shivers down my spine as mysterious hooded figures in djellabas loped through the night shadows.

There we reveled in tangy tagines or sizzling lamb kebabs grilled on braziers as well as mountainous platters of couscous. Our first sampling of the this grain came after a breakdown in the Rif mountains where we were warmly served a banquet by the Number One Widow of the village before bedding down on divans in her front room. Young and impressionable, I never forgot this first taste of either Morocco or Andalucía – or was it both: Al-Ándalus?

A few years later I was back, this time to a tiny village called Sorbas, near Almería, that had barely emerged from the Middle Ages let alone from Franco’s rule, which had only just ended. Fresh from an energising holiday in New York, I had come to join my French artist-boyfriend for a complete change of scene and pace, much helped by Sorbas’ dramatic cliff-top site above a primeval, eroded landscape. As Almería airport was military at the time, I had taken the very basic night-train down from Madrid that only left memories of a dark, empty land pinpricked by the odd light.

It was late autumn, meaning that in the village the annual matanza (slaughter) was kicking off. Every morning, agonizing squeals rang out as the fattened pigs met their makers, hardly romantic, but at that stage I had no idea about the resultant joys of jamón, salchichón or chorizo. While monsieur wielded his paint-brushes or cogitated in a hammock on the roof terrace, I would set off with my camera to try and record this timeless place. Inquisitive faces framed by black headscarves peered out from tiny square windows but it was the monumental karst landscape sliced by canyons and speckled with sculptural cacti that electrified me.

In fact this desert of Almería, more precisely Tabernas, had already been discovered by a stream of film-makers, soon becoming the location of choice for every spaghetti Western ever made. Not only that, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ rode his camel through the canyons, John Lennon adopted his trademark round glasses for “How I won the War” and a few years before I arrived, Antonioni had filmed part of “The Passenger” with Jack Nicholson. One evening, Sorbas’ eccentric bar-owner, Juan of Bar Fatima, proudly described his 15 seconds of fame in the movie (he limps outside the bar to mumble one line to Nicholson), before regaling us with stories of an Ash Wednesday procession which brought him a far bigger role in the traditional ‘burial of the sardine’. “And I lifted up the sardine for God!” Thus I discovered surrealism, Andalucian-style.

RIVETING: Andaluz – a Food Journey through Southern Spain, Fiona Dunlop’s hotly anticipated new work

Gastronomy in those days was a mere afterthought, as rural Spain, in particular impoverished Andalucía, had hardly advanced since the hardships of the Civil War. Sorbas’ two grocery shops were woefully basic and I was shocked to find no butter, a product of the greener north that was alien to Andalucía. Instead there was a tasteless spread called Tulipan, which still exists. Of course now, better informed, I know olive oil is a healthier substitute, though back then an inferior oil was rather too ubiquitous, drenching just about any tapa in the roadside bars, and the ‘extra virgin’ tag was more usually applied to Mary. The village shops only stocked lard or cheaper blends of oil, though no doubt there was a private network supplying the good stuff. Even vegetables were sparse in that desert area, so low-grade pasta, pork chops and tinned sardines became our culinary mainstay – hardly gastronomic.

Yet there were revelations. The postman told us all about gathering and preparing snails (“put them in a covered bucket and purge them on flour for 48 hours”), a prelude to bringing a bagful of the live beasts to cook for us. They were tiny, but delicious, and far tastier than the larger, meatier ones I had sampled in France. Years later I was thrilled to find hundreds of the Andalucian species crawling around a huge basket in the R’cif market in Fez, destined for ghoulal, snail soup.

One evening we were invited to dinner by the Sorbas butcher in his shop along with similar village dignitaries. Here, amongst other tasty (piggy) victuals, we were rather formally presented with a huge pan filled with… goat’s head soup. Little did they know about the Rolling Stones album, released a few years earlier – or perhaps they did? When encouraged to eat the goat’s eyes, said to be the greatest delicacy, I demurred, but the cheeks were a treat.

Fast forward a few more years and I was making full use of my parents’ holiday house by the sea in Mojácar, not that far from Sorbas, but seemingly light years away. By then Spain’s movida (post-Franco cultural revolution) was in full swing, and life in this cosmopolitan beach community reflected it. In the 1960s, the canny local mayor of what had become a semi-abandoned hill-village had offered free houses to anyone who was prepared to restore them. Soon a stream of artists and artisans flocked there to shape a lotus-eating spirit against a backdrop of the glittering Med.

When I first lived there, older women in long black headscarves frequented the village fountain to collect drinking water and wash clothes, while others pulled donkeys laden with home-grown veg to the village market. One, María, always looked out for me: “Hola guapa!” she’d cry as I came to pick through her misshapen vegetables. I still remember her huge, green-tinged tomatoes, nothing like I had ever seen or tasted in Paris or London. In fact Almería’s sandy soil was where the cross-bred Raf tomato originated at about that time, now a chef favourite.

This, too, was where I discovered the joy of fresh Mediterranean fish, from gleaming sardines to slippery silvery anchovies (laborious to clean but so delicious dusted in flour and fried in olive oil) to more delicate red mullet. Every afternoon at 4pm, I could set my watch to the fishing-boats chugging home to Garrucha, the nearby port, while I fantasized over what piscine treasures filled their holds. Of course I was never up in time to see them leave at dawn.

Occasionally the sybaritic rhythms of Mojácar life switched to melancholy when, on a late visit to a bar, a trio of local gypsies from nearby Turre would break into searing cante jondo, feet tapping, knuckles rapping the counter and hands clapping in syncopation. Luckily, robust carajillos (black coffee drowned in brandy) steadied our emotions, and that elliptical Andalucian chatter soon replaced this atavistic howl of deep longing. Slowly I was getting used to the guttural chopping and dropping of syllables, mashing others together, a language totally foreign to any self-respecting Castillian.

As the years rolled by and Spain entered its golden E.U. era, attracting vast subsidies, sprawling developments, motorways and rampant corruption, the old-timers gradually disappeared. A few shepherds and goatherds remained, their protégés skipping round the hillsides to nibble tufts of herbs between carob trees, aloes and yuccas, but otherwise life focused increasingly on tourism. Luckily that brought a few positive changes to this seductive pueblo blanco splashed with bougainvillea. Small, foreign-owned restaurants popped up in the narrow backstreets bringing couscous and even Persian dishes, while hip bars became well-imbibed social hubs to while away the long hot nights.

Summer after summer I would cruise down from my home in Paris in an old Mercedes laden with books, notes, my laptop and a fax machine (this was pre-Internet) to write travel guides about exotic countries I had just travelled to. Between swims, siestas and socialising, my focus during the long, scorching, silent afternoons was on countries like Indonesia, India, Vietnam or Mexico. In the midst of my vagrant, globe-trotting existence, Andalucía had become my anchor, my home.

However by the turn of the millennium my life had changed, I moved back from Paris to London, my parents died and the Mojácar house was sold. I felt bereft.

I continued to travel regularly all over Spain to write travel features and books, as I did to North Africa, mainly Morocco but also Tunisia and Libya, and to the Middle East, but I missed that deep connection with the land. “Es tu tierra!” (it’s your land) as a local builder once said to me, holding up a fistful of soil. Once, after driving from Extremadura into Andalucía, I realized how sensorial was my attachment when I entered a village bar to be dazzled by a chaotic patchwork of patterned tiles, whiffed garlic sizzling in olive oil, heard a cheeping canary and was instantly served a saucer of crisp fried fish with my caña. It was all about lightness, simple bounty and good cheer – and it felt like home.

Finally, after scouting around villages from the Cádiz coast to the Alpujarra mountains, I plumped for a country house in a little known, mountainous region between Granada and Córdoba: the Subbética. In fact it’s the geographical heart of Andalucía, although I didn’t know that. My house hugs the edge of a hamlet of olive-farmers, all deeply rural in spirit, with none of the gloss that Mojácar eventually acquired. Life slows to a crawl here. My long terrace faces hills carpeted in olive trees ending at the distant snowy peaks of the Sierra Nevada, while far below in the other direction is the village of Iznájar, topped by a Moorish castle that remained a stronghold of the emirate of Granada virtually until its capitulation. The name itself derives from the Arabic hisn ashar meaning ‘happy castle’. A welcoming place indeed.

Days here are calm and uncomplicated, the perfect antidote to London’s fast lane. It is still a deeply macho society where men monopolize the bars and women labour at the stoves or marshal the kids, while the young are high-tailing it elsewhere. Yet I can’t help but I love the bountiful produce at the local markets, the homemade salchichón , the sweet, juicy winter oranges, the luscious green olive oil, the morning fish from Málaga sold out of the back f one van, and the freshly baked bread out of another.

Above all I love my neighbours who turn up with bags bulging with peppers, tomatoes, figs, walnuts or apricots fresh from their huertos, I love the old boys in flat caps (mostly called Antonio) chatting on benches who always nod hola or buenas as we pass by, I love the shifting shadows and darkening clefts of the sierra, the dramatic skyscapes, the vast, twinkling night skies, the autumnal clouds that drift through the valley before dissipating into clear, golden light, the swooping, screeching swifts and swallows, the purple and yellow wildflowers that cloak the groves in spring, the stirring Easter processions and zany village ferias and fiestas, the blistering hot days of summer when we swim in the reservoir-lake of Iznájar, the frenetic energy of the olive harvest culminating in the lingering smell of woodsmoke in winter when the village mills rattle away long into the night.

So this book, in search of Al-Ándalus through its culinary legacy, is my ode to the entire region – its momentous past, bewitching landscapes and its charming, garrulous, truly egalitarian, often surreal and ever generous-hearted people, who are masters of alegría, of high decibels and of setting the taste-buds alight.

Published by Interlink Books, USA www.interlinkbooks.com

Keep up to date with Fiona’s latest work at www.fionadunlop.com, Facebook: fionadunlopfoodandtravel and Instagram: @ffdunlop